The poet Pablo Neruda fittingly referred to watermelons as the “green whale of summer” in his poem, “Ode to the Watermelon.”

Watermelons are indeed a staple of summers, and their green, white, and red fruit – filled with wild rivers of sugar – have delighted taste-buds for thousands of years. Watermelon seeds have even been discovered in King Tut’s tomb.

Watermelons (Citrullus lanatus) belong to the cucurbits or the gourd family (Cucurbitaceae), which also includes familiar relatives such as the squash, pumpkin, cantaloupe, and cucumber.

Watermelon Plant Care

Watermelons are long-season, frost-sensitive annual vines, and they sometimes require up to 80-100 frost-free days to mature and bear fruit.

They also need to be replanted and rotated every year to grow new fruit and to keep soils fertile and disease-free.

Watermelons are not particularly hard plants to care for, though they do have specific needs: full sun, warm temperatures, plenty of moisture, growing space, organic matter, and occasionally assisted pollination.

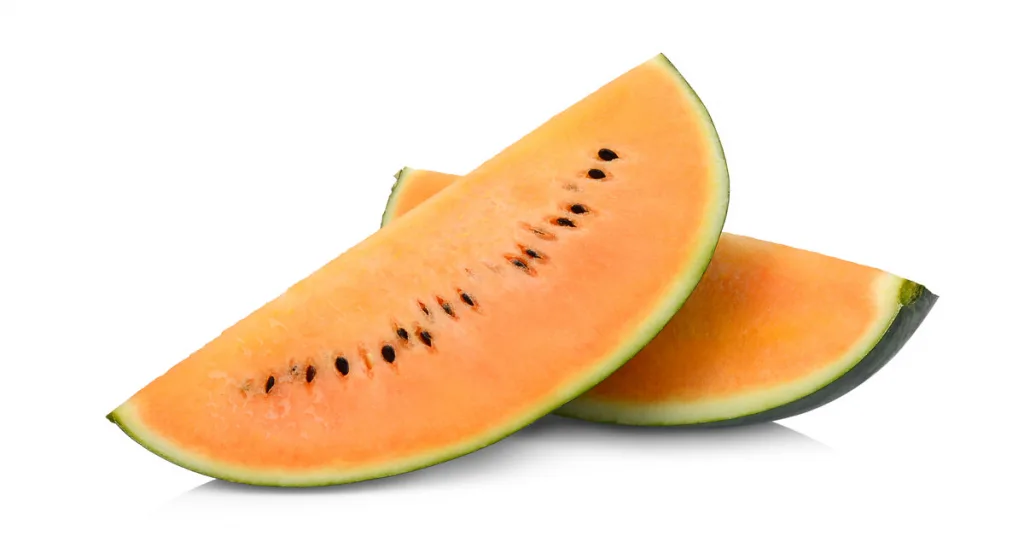

Watermelons are also very nutritious, and come in many sizes, colors, patterns and varieties, including seedless and disease-resistant cultivars.

Below, we’ll go over everything you need to know about growing delicious and nutritious watermelons and more.

Soil

Like cucumbers, watermelons prefer warm, well-draining, slightly acidic (pH 6-7) soils with lots of organic matter. Watermelons grow best in mounds about 6-12 inches (15-30 cm) tall.

Watermelons prefer dry feet, so consider growing on raised garden beds if drainage is an issue.

Avoid manure, as it may contain harmful bacteria and increase weeds.

Watering

Watermelons require daily watering during the germination stage.

However, after seedlings have developed, water deeply and infrequently (allowing top soil to dry between waterings), about ~1-2 inches (2.5-5 cm) of water every week.

Reduce watering when approaching harvesting time to prevent fruits from splitting and better flavor.

Water from the bottom, and consider drip irrigation or a soaker hose to avoid getting leaves wet, which invites fungal infections on leaves.

Lighting

Watermelons need lots of warmth and full-sun to thrive.

Ideal spots in the garden are on south-facing or west-facing slopes for maximum light.

Temperature & Humidity

Watermelons grow best at average temperatures between 70-85°F (21-29°C). Temperatures above 95°F (35°C) and below 50°F (10°C) will inhibit growth and fruiting.

Watermelons are extremely tolerant of a wide range of humidities, and can grow in both humid and semi-arid environments.

Excess humidities and lack of airflow, however, may invite fungal diseases.

Store harvested fruits, however, in temperatures between 50-59°F (10-15°C) and with relative humidities between 85-90% for best keep.

Fertilizing

Watermelons are heavy nitrogen-feeders so consider amending the soil with nitrogen-heavy composts such as blood meal or alfalfa meal before seeding.

After vines develop, side dress each plant with 3-4 tablespoons of fertilizer heavier in nitrogen than phosphorus and potassium to encourage foliage growth.

After flowering, however, apply a fertilizer with less nitrogen to emphasize fruit growth.

Diseases & Pests

Weeds are usually not a problem, as fast-growing watermelons tend to shade out competition from weeds. Consider mulching with grass clippings if weeds are a problem.

Watermelons are susceptible to the following diseases:

- Anthracnose – Watermelons are very susceptible to this common fungal disease, which causes small, brown-black (or gray) spots to develop on young leaves and fruit, killing stems and leaves.

- Downy mildew – This fungal disease shows up as pale green to yellow blotches on older leaves. These blotches then develop into circular to irregular dark-brown to black spots. Affected leaves will yellow, then brown, before curling and dying.

- Powdery mildew – This disease will appear on oldest leaves as yellow areas on the upper leaf surface. White powdery mildew will also often form on the undersides. Affected leaves will die and fruits may also develop symptoms.

- Fusarium wilt – This disease causes root rot and vascular wilting, which causes stems and leaves to yellow and brown before wilting. Spores may last for years in the soil.

- Gummy stem blight – This disease causes leaves to develop circular to irregular dark brown to black spots. Spots often develop at leaf margins, causing foliage death and sometimes fruit rot.

- Papaya ringspot virus, watermelon mosaic virus, and zucchini yellow mosaic virus– : These viruses all affect watermelons and cause stunted plant growth and abnormal fruit development and reduced yields. Symptoms include misshapen, puckered, and pale leaves. There is no cure for viruses, though avoiding pests and weeds (vectors of transmissions) is key to prevention. [1]

For fungal infections, there are a number of ways to prevent and control, including crop rotation, fungicides, sanitation, proper irrigation, or planting disease-resistant cultivars.

Watermelons are also susceptible to pests such as : cucumber beetles, nematodes, vine borers, aphids, and mites, which spread disease and drain nutrients.

Treat with insecticides or cover plants with reflective plastic mulches, which repel aphids before they infect fruiting plants.

Planting a protective row of summer grasses such as grain sorghum (or other companion crops) will create a “virus sieve,” which helps intercept aphids and other pests.

Harvesting and Days to Maturity

Watermelons are long-season crops which take anywhere from 80-100 days from planting to harvesting, depending on the cultivar.

Below are the approximate watermelon plant stages and lifespan:

- Germination: Once planted, seeds will send out a stem (also called a hypocotyl) and root (also called a radicle). In 3-12 days, stems will push forward two embryonic leaves above the soil surface.

- Vining: 5-10 days after germination, the first true leaves capable of photosynthesis will emerge from the stem. A vine will also develop with large lobed leaves and grow up to 12 feet long over the next few weeks. About a month after this vine developing, several more vines will begin to develop and grow leaves.

- Flowering: About two weeks after your watermelon develops all its vines, it will begin producing male and female flowers. Male flowers will emerge first, providing pollen to the female flowers that soon follow.

Viable flowers only bloom for one day, so it is essential that pollinators such as bees are nearby. If not, hand pollination – brushing the pollen onto the center of female flowers – may be necessary.

- Fruiting: Fruit will begin developing after pollination and take one month to reach maturity.

- Harvesting: Tendrils will change colors from green to brown as the watermelon ripens over a two week period. The spot on the watermelon where it touches the ground will also turn from white to yellow.

Slap the watermelon and listen for a hollow sound, which indicates ripeness. Overripe melons, however, may explode or crack so be sure to harvest when ripe.

Ripe melons also only last a week at room temperature, or two weeks in the fridge.

Watermelon Origin

Watermelons were believed to have been first domesticated in North Africa, where they have been cultivated for thousands of years.

Depictions of watermelons have appeared on Egyptian tombs dating as far back as 3,100 BC. The Egyptians referred to watermelons as bddw-k.

However, genetic evidence and the presence of wild varieties indicate watermelons may have originated in western, central, and southern Africa, where wild watermelon ancestors have existed for millions of years.

From North Africa, watermelons traveled to North Africa, India, and onto Asia in the first millennium BC, before spreading to Europe and the New World thereafter. [2]

How to plant watermelon

Watermelons may be planted from seeds or from starter plants purchased from nurseries, which give a headstart on the growing season.

Seedlings usually need to be hardened off before planting outdoors.

To harden, gradually introduce seedlings outdoors, as long as temperatures are above 65°F (18°C) for a few hours.

Keep them on a porch or ledge protected from winds, and take them in at night. Do this a few times until they are ready to be permanently transplanted.

To transplant, take them from the pot or starting tray. Do not shake dirt off roots.

Dig holes that are the same size as the plant and build a little mound for each seedling to grow on. Watermelon plant spacing should be 4-6 feet apart to ensure room for vines to spread.

Water after planting, but do not soak the soil. Depending on the soil, amend with compost to encourage faster growth.

If planting seedless varieties, be sure to plant a seeded variety alongside, as seedless watermelons cannot self-pollinate.

How to grow watermelon from seed

If direct seeding, wait until soil temperatures are at least 65°F (18°C) or warmer, one week after the last frost before sowing.

Place 2-3 seeds per hill, about 1 inch (2.5 cm) deep and 4-6 feet (1-2 m) between each hill. Plants can spread 6-12 feet (2-4 m), so are often grown in rows if growing many together.

Water seeds thoroughly daily until seedlings emerge, but do not soak. Thin seedlings to the strongest one per hill.

Seeds can also be started indoors if you live in colder climates.

Types of watermelon

There are hundreds of varieties of watermelons available, from species which are small, hard, and bitter, to the well-known large, juicy, and sweet types.

Many human-made cultivars have also been created which are disease-resistant, seedless, and transport-proofed.

Watermelon varieties are grouped into three types: open-pollinated, F1 hybrid, and triploid or seedless types.

Open-pollinated seeds bear seeds which create true to type plants and are self-pollinating. These seeds are often the cheapest, as they do produce naturally without extra labor.

F1 hybrid seeds are often more expensive, as they have been engineered and bred to be more disease-resistance and produce better yields. However, new seeds are required every year, as the seeds produced from F1 plants do not grow true to type like open-pollinated varieties.

Seedless watermelons are created by doubling the usual chromosome number and crossing with normal watermelon plants. Plants with double the chromosomes cannot produce fully develop seeds. Seedless watermelon seeds command a premium price in the market. [3]

Watermelon Cultivars

Besides seeds, watermelons are also grouped according to fruit shape, rind color or pattern, and size.

For example, large oblong watermelons with dark stripes in the 25-35 lbs (11-15 kg) range are often referred to as Jubilee types.

Melons similar in size to Jubilees but have a lighter green rind are called Charleston Gray types.

Round melons between 20-30 lbs. (9-14 kg) with striped rinds are referred to as Crimson Sweet types.

Allsweet Watermelons are between 15-25 lbs (7-11 kg) and have green rind with light yellow striping and dark sweet flesh.

Lastly, icebox watermelons refer to those smaller than 10 lbs (4.5 kg) and fit easily into refrigerators.

Watermelon Benefits

Watermelons offer many nutritional benefits, including being a good low-acid fruit. The average watermelon pH level is 6.2 and may go higher when fully ripe.

Combined with over 91% water, watermelon fruit can help reduce the harmful effects of acid in your bloodstream and regulate pH, which some claim may prevent diseases such as cancer and heart disease. However, this claim requires more research to verify.

Regardless, watermelons, including edible rinds and seeds, do offer a number of beneficial nutrients that have been long studied:

| Key Nutrients | Purported Benefits |

| water | Hydration and body temperature regulation |

| fiber | Aids in digestion and beneficial for teeth and gums |

| citrulline | Relaxes blood vessels and supports nitric oxide synthesis (which is believed to help with male sexual functions and cardiovascular health) |

| arginine | May help improve blood flow and reduce accumulation of excess fat |

| lycopene | Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory known to help prevent prostate, breast, and lung cancer |

| vitamin A | Great for skin; Benefits vision and immune systems |

| vitamin B6 | Important for brain development and keeping nervous and immune systems healthy; help with morning sickness and premenstrual syndrome |

| vitamin C | Antioxidant that protects from cellular damage; strengthens immune system and may help lower blood pressure |

| potassium, magnesium, iron | Helpful for regulating blood pressure; promotes heart health |

| beta-carotene and phenolic antioxidants | Helps with immunity, skin, eye, and cancer prevention |

For exact amounts and full nutritional list, see USDA FoodData Central.

Studies have also shown that more ripened watermelons will also have greater presence of beneficial nutrients such as lycopene and beta-carotene, so be sure to let your watermelons ripen.

Watermelon Companion Plants

Watermelons benefit from a variety of companion plants:

- Flowering plants such as okra, marigold, and lavender attract bees, which help pollinate watermelons, and repel pests.

- Corn may provide extra shade for fruits, especially in hot climates.

- Hot petters help form a pest barrier.

- Summer grasses such as grain sorghum create a “virus sieve,” as they intercept disease-spreading aphids and other pests.

- Legumes (e.g. peas, beans, peanuts, clovers, and lentils) are nitrogen-fixing and increase soil organic matter, and are great companion plants for nitrogen-demanding watermelons.

- Some herbs such as catnip, chives, dill, mint, nasturtiums, and oregano also help repel pests.

- Root vegetables such as radishes, garlic, beets, turnips, parsnips, carrots, and onions are great with watermelons, as they grow underground, do not compete for space, and are ready to harvest before watermelons. These root vegetables also repel pests and loosen soils.

Other melons, cucumbers, zucchinis, potatoes, pumpkins, and squash should be avoided or rotated, as they also invite similar pests which can then spread.

Watermelon vs Melon (Cantaloupe)

Cantaloupes are a type of muskmelon (Cucumis melo) belonging to the gourd family (Cucurbitaceae), which includes relatives such as the watermelon, pumpkin, squash, and cucumber.

Though related, watermelons (Citrullus lanatus) are actually more distantly related than cucumbers are to cantaloupes, as watermelons belong to an entirely separate genus called Citrullus.

References:

[1] Damicone, J., & Brandenberger, L. (2020, June). Watermelon Diseases. Oklahoma State University Extension. https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/watermelon-diseases.html# fusarium-wilt-fusarium-oxysporum-f-sp-ni.

[2] Lovegren, S. (2016). Melon: A Global History (Edible). Reaktion Books.

[3] Boyhan, G., Granberry, D., & Kelley, T. (1998, November). Commercial Watermelon Production. University of Georgia Extension. https://secure.caes.uga.edu/extension/ publications/files/pdf/B%20996_4.PDF.